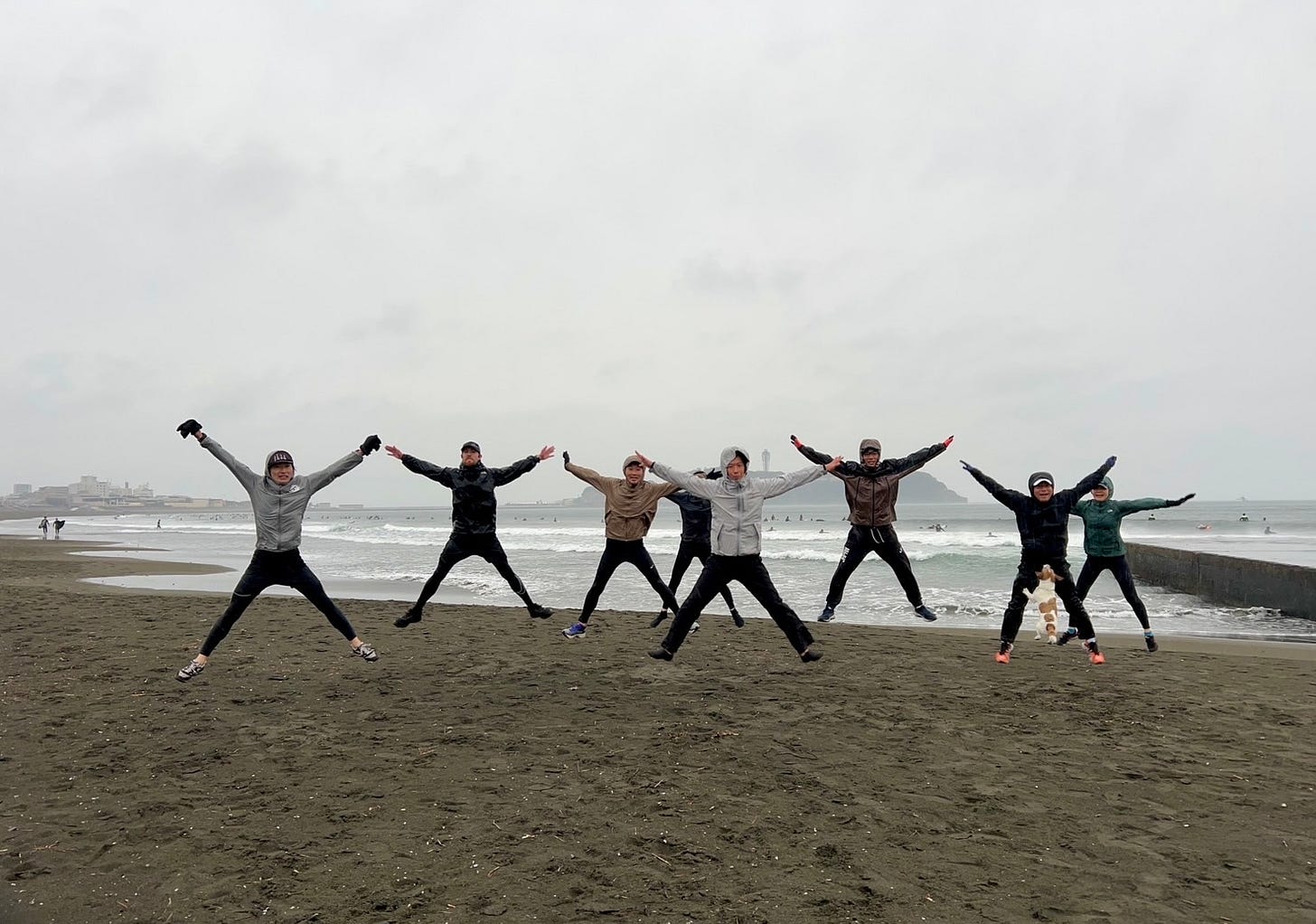

Fair weather runners

In 2021 I ran 3,650 km. For those who are (very) bad at maths, that’s an average of 10 km per day. Some days I ran a bit more, some days I ran a bit less. But on average I managed to get to 10 km a day.

I started running in August 2020, so I was still a relatively new runner then. But I set out to do this task and to get it done I needed to adapt to a lot of conditions.

People who have experience with Japan will know that “Japan is a four season country.” But the devil is in the details.

The UK is a four season country as well. We have spring (pleasant and rainy), summer (occasional sunlight and rainy), autumn (cool and rainy), and winter (cold and rainy). But the seasons in Japan are a bit more pronounced.

In Japan there seems to be a hard line drawn on calendars. Once you cross this specific date you can set your watch to a weather phenomenon happening:

春 (haru: spring): Cherry blossoms and pleasant weather

夏 (natsu: summer): The sun is trying to kill you. You can cook eggs on the floor. It’s so hot you can hear the air.

秋 (aki: autumn): The leaves change colour and the weather is pleasant.

冬 (fuyu: winter): The cold gets directly into your bones. Houses are not insulated. You will forget what warmth feels like unless you go to a hot spring.

There is of course a fifth season (that Japanese people will not acknowledge as a proper season) called 梅雨 (tsuyu: rainy season). This occurs between spring and summer and is a season where everything is wet all the time regardless of rainfall and the shelf life of bread halves.

In 2021 I got it in my head that I could not be a “fair weather runner.” Fair weather runners are people who only go out when conditions are ideal. If it rains a bit they’ll stay home. If it’s too cold they’ll stay home. If it’s too hot they’ll stay home. If I was a fair weather runner it’s likely that I would only run in spring and autumn, so I needed to get used to sucking it up and running no matter the conditions.

Efficacy vs effectiveness

This blog is called 文武両道 (bunburyōdō) because of my life focus on the balance between academics and athletics. But most of the time my blog focuses on the sports side of things (with the occasional bit of linguistics thrown in). Today I’m going to be explaining something a bit more interdisciplinary.

Over my life, education, and career, I’ve been involved in science. In particular, I’ve been involved with clinical research. To give you a very brief breakdown of the clinical trial process, when a new potential drug is going to be tested, it’s first tested in a small group of healthy volunteers for safety (Phase I), it’s then tested in a selected patient group for more safety and small scale efficacy (Phase II), that group is expanded to large scale efficacy (Phase III), before eventually being monitored for safety and effectiveness in the general population (Phase IV).

You might notice that I highlighted efficacy and effectiveness in the previous paragraph. Both of these words mean something very similar, and (frustratingly) in Japanese the word 有効性 (yūkōsei: have effect) is used to describe both concepts. (Note that additional descriptors tend to be added to contextually explain the differences when writing in Japanese).

My understanding of the difference between efficacy and effectiveness is the circumstances in which an effect occurs. If the effect occurs under ideal, controlled circumstances then it is classified as efficacy. An example of this in a clinical trial would be to test out a new drug in 20-50 year old males who have no other conditions. Meanwhile effectiveness is when the effect occurs under general circumstances where no control occurs. A professor of mine in the UK described effectiveness of some medicines with the following: “While some drugs only work in specific circumstances, others are effective no matter the situation. If I gave you a pint of caster oil, you will shit*.”

*Probably not a good idea to mess with this professor.

After I learned about efficacy and effectiveness I’ve tried to apply the concept to things outside of research and more in relation to life.

Are your martial arts effective?

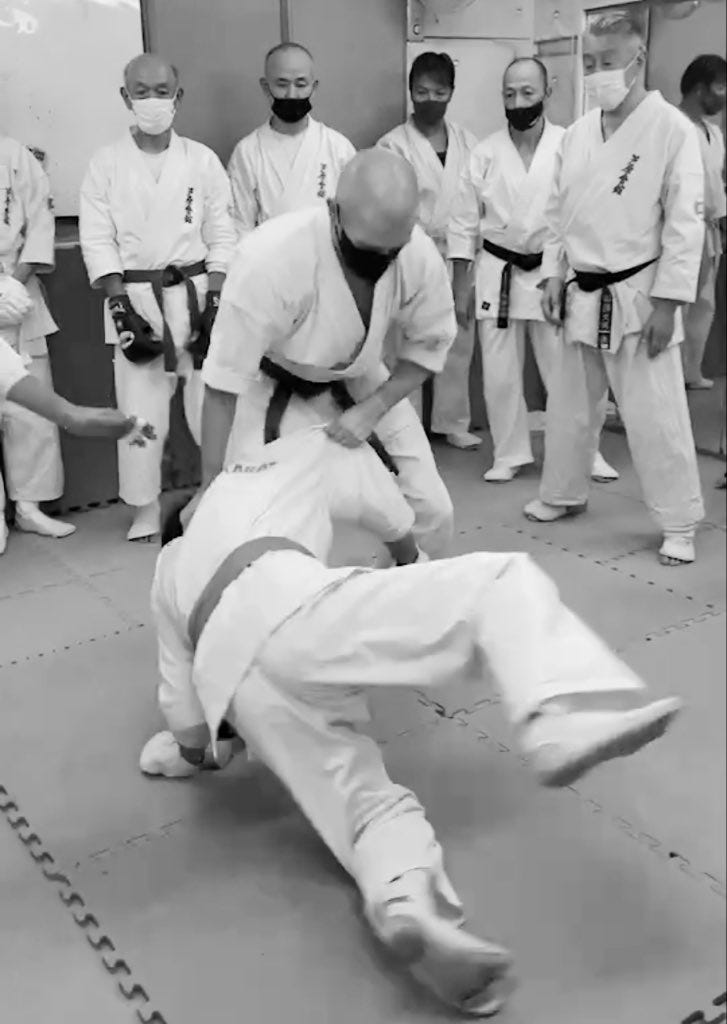

A sort of holy grail for people who practice martial arts is to be an effective fighter. Many people might not phrase it like that, but that’s essentially what they are talking about when they are talking about being “good” at fighting. But a lot of martial arts get stuck in this “efficacy” bubble and they might not even realize it.

As someone who practices karate I generally train in bare feet, wearing a uniform I can easily move around in. I train on hardwood floor or mats, and I train with people who have agreed to train with me under a particular rule set which necessitates certain protective gear and prohibits certain techniques.

A few weeks ago I was training and a relatively new guy (who has experience in other styles) decided that he was going to fight (not spar, fight) everyone during a round of light sparring. He was throwing 100% power into every technique and really trying to hurt people. I was trying to keep it light and was just blocking his techniques until he threw a full power kick at my head. I blocked it with an 上げ受け (ageuke: rising block) taking all the power out of the kick but his toenail caught my ear and left a cut. Right after this happened I thought to myself, “That’s not ideal,” and knee’d him in the sternum to make him “calm down.”

The circumstances I describe here are still in a relatively controlled environment but things were really going off script and moving more into a circumstances where not being effective will lead to injury.

When you learn to swim it’s a good idea to try swimming fully clothed to make sure you really swim if you happen to accidentally fall into a body of water. If you can do that you are an effective swimmer. The same can be said for martial arts. Yes, you can spar at the dōjō, but can you fight in your regular clothes?

One interesting thing to point out about this is that the style of karate I practice (Ashihara karate) seems to be quite popular in cold countries. The thick 上着 (uwagi: jacket) of an Ashihara karate uniform is often used in techniques (grabbing and dragging is allowed), and thus may mimic what people wear outside the dōjō. Meanwhile, (MALE) Muay Thai practitioners go bare chested and as such there are no clothes to grab onto and use in techniques (just like in Thailand where no one is wearing a heavy jacket in the streets). Because of this I’m convinced that there are some martial arts that train you better for getting into a fight in the heat and others that are better at training you to fight in the cold. But that’s just me.

Fail to prepare, prepare to fail

I’m a hybrid athlete and as such I train in a lot of different areas. Martial arts aside, I run…a lot.

I enter a lot of different races and not all the races are the same. The most simple race I’ve entered is a 5K around a flat park on a nice day. The most complex race I’ve entered was a 100 mile (160 km) run that had me running through many different kinds of terrain and up two mountains with the risk of sunburn on the first day and the risk of hypothermia the second (see Yagurazawa Ōkan).

One of the best races I’ve ever run was the Izu Trail Journey. One of the reasons I liked this race so much was becase of the very strict rule set that they had. There was a long list of things you needed to carry with you at all times including things like a first aid kit, emergency blanket, two headlights (with spare batteries), at least 1 liter of water, rain gear, etc. Although it seems like a pain to carry all of this stuff, it was against the rules not to carry it and you could be disqualified from the race if you got checked and didn’t have the required kit with you.

Because I knew that Izu had this equipment list, sections run in the dark, and unpredictable weather, I did my best to practice by doing as many runs as I could that could simulate the conditions of the race. This meant a lot of running up trails in the woods, carrying all my gear, and making a conscious effort to go out there in the dark and the rain to get the appropriate training done.

I’ve heard the phrase, “Fail to prepare, prepare to fail,” many times before but it was running the Izu Trail Journey that made it a mantra for me. Not just for that race but for all of the others I’ve run since. If you don’t prepare yourself for the conditions you might come across, you may not be able to deal with the problems you face. Sometimes we can get over problems by improvising on the fly and working it out. But being prepared to dealing with a situation will always be superior to mere improvisation.

Final thoughts and take home messages

If you are an athlete that specifically focuses on 5K runs and only ever runs on an indoor track then it is probably ok to focus your training on being the best you can be at middle distance indoor track running. But for me (and many others) there are a lot of difference circumstances we might come across.

I would love it if every race I ran and every challenge I come across presented me with ideal conditions. If every day was a cool, dry, autumn day life would be easy. But perfect conditions have a tendency to not be there when we want them, so we need to prepare to be effective, regardless of what is thrown at us.

The more you can train to deal with situations where things go off script the better. If you have a marathon coming up and you’ve never run in the rain before, you can either pray that it doesn’t rain or start training in the rain to get used to it before the big day. That way you’ll be prepared no matter what the weather is.

Fail to prepare, prepare to fail.

I don’t want my readers to fail. If you come across a situation you are unprepared for, I hope you are able to improvise your way out, learn from it, and approach it with the knowledge of how to do it better next time. But to completely avoid those situations, I hope you will consider the above quote and really make an effort to prepare yourself as best you can so you can deal with everything that life throw at you.

Thank you very much for reading. If you enjoy my work please share it with someone you think would also enjoy it.

If you aren’t subscribed, please sign up to keep up to date.

If social media is more your thing I’m active on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

And if you are looking for ways you can support my work please check out the page below:

Osu!

Anthony