Studying Japanese: Where to begin (文武両道)

Embrace the grind

This article is meant to provide some hints and tips on how to learn the Japanese language. My Substack isn’t specifically about studying Japanese. I can just speak Japanese, discuss Japanese concepts in my writings, and I’m aware that there is a demand amongst my readers for some help with this.

This article is going to be split into a few parts:

1. Introduction (if you’re interested…)

2. Characteristics of the Japanese language

3. How I studied Japanese (and why it might be difficult to replicate)

4. Strategy and resources

5. Japanese qualifications

6. Final thoughts

My comment section is open if you have any questions about the content.

1. Introduction (if you’re interested…)

Back when I was in high school I was required to learn some French and some German. I was not good at either of these languages, and because of that I had it in my head that I just didn’t have a natural talent for languages. In reality, the main reason I was no good at French/German in high school was that I was just not interested and therefore didn’t apply myself.

I have a belief that if you aren’t interested in something it becomes much more difficult to learn. Conversely, if you are interested in something, you are more likely to stick to it and become successful.

In this article, I’m going to go over a few pointers on how to start learning Japanese. Note that I am not going to hold your hand through the process. I am just going to point you in the direction to get started.

2. Characteristics of the Japanese language

A lot of people say that the Japanese language is difficult to learn. That is absolutely, not useful information. Rather than asking Google about whether the language is difficult or not, it’s better to consider the characteristics of the language.

Script

Japanese is made up of three character sets. ひらがな (Hiragana) is what I would call the curved, phonetic script used for (mostly) words of Japanese origin. カタカナ (katakana) is what I would call the blocky, phonetic script for (mostly) words of non-Japanese origin. 漢字 (kanji) are Chinese characters that convey both sound and meaning.

Many people say that Japanese is difficult because it has three sets of characters. This is not correct. Hiragana and katakana are phonetic characters and therefore, once you learn the sounds that they make there is nothing left to learn. A hiragana か (ka) is pronounced ka in every situation. Yes, there are examples of composite sounds where characters like き (ki), and や (ya) can be combined to make きゃ (kya), but it’s not comparable to some of the abominations that go on in the English language.

The difficult part of Japanese script comes in the from of the kanji. Generally kanji are read differently depending on the context they appear in a sentence. There are 音読み (on yomi: Chinese readings), and 訓読み (kun yomi: Japanese readings) of characters. Some kanji have multiple on readings and multiple kun readings (in addition to some other special readings) and this is what a lot of people seem to get stuck on.

But it’s not all bad news.

Tones and pronunciation

Some languages have tones and pronunciations that can fundamentally change the meaning of a word. Japanese is not like this. It’s relatively monotone in comparison to truly tonal languages like Mandarin or Thai and is largely pronounced as it is written using phonetic characters. Context is usually enough to get the desired meaning across. (Note that pitch accent is something that exists in Japanese but personally, I don’t think beginners need to focus on this much).

If you say しょ (sho) instead of ちょ (cho) you will probably be misunderstood. These pronunciations may sound similar to some people but they are distinctly different in Japanese. Also, there are examples of long and short sounds like きょ (kyo) and きょう (kyou or kyō), which may cause some confusion but may be understood based on context.

Don’t stress out about these too much. They come with practice.

Verb conjugations are important!

In Japanese verbs conjugate in several different ways depending on the structure of the word. The meanings of words often revolve around the way a verb is conjugated. For example, if I take the verb 食べる (taberu : eat), and the word 餅 (mochi : a kind of rice cake) and add some example sentences:

餅を食べる (mochi wo taberu) : Eat mochi (dictionary form)

餅を食べます (mochi wo tabemasu) : Eat mochi (masu form, polite)

餅を食べた (mochi wo tabeta) : Ate mochi (ta form, past tense)

餅を食べたい (mochi wo tabetai) : Want to eat mochi (tai form, expressing desire)

餅を食べない (mochi wo tabenai) : Don’t eat mochi (nai form, negative)

The last one especially is a bit odd. You are more likely to say, 餅を食べないでください (mochi wo tabenai de kudasai), which means, please don’t eat the mochi.

Note: This isn’t a full list of all the ways to conjugate. Just a few examples.

When I was learning about verb conjugations I learned the names of the verb types like 一段活用動詞 (ichidan katsuyou doushi : Type 1 verbs), and asked my Japanese colleagues about them. But native speakers who aren’t Japanese teachers don’t seem to know much about the names of the language structures. (I’m the same when language learners ask me about complex linguistic mechanics of the English language). It just comes naturally to them so you are going to need to study this a lot (because it’s important) but you are going to need to rely on appropriate study materials to do so.

Particles

Finally, particles are parts of the Japanese language that stick sentences together and denote things like prepositions. I am not going to go too much into this part because I think you need a textbook to understand this properly, but particles like は (wa), が (ga), の (no), に (ni), を (wo), etc, are important grammatical structures that hold the language together.

Get a textbook to understand these. Although there probably are ways to study these things online it might be better to focus on one structured course to learn all the basics in one swoop and then do supplementary learning later.

There are a lot of other characteristics of the language but I think I covered the important ones.

3. How I studied Japanese (and why it might be difficult to replicate)

I came to Japan in 2006 with almost zero Japanese. I took a very brief language course (1 week) in the UK before coming to Japan and the result of that was that I couldn’t read anything, but I could order a drinks.

I was working on an exchange program called the JET (Japan Exchange and Teaching) Programme (link here) and I was provided with some basic language textbooks. Some people on JET study, some don’t. I went in with the attitude that it was my job to use any downtime I had to study Japanese so that’s what I did.

The textbooks I was given had readings for everything in English but I was told it was a good idea to stop using English as quickly as possible. For the first few weeks I drilled hiragana and katakana by writing everything out over and over again on a big pad of paper until I pretty much remembered all of the phonetic characters. I didn’t get them perfect every time but I knew them well enough to be able to use my textbooks properly.

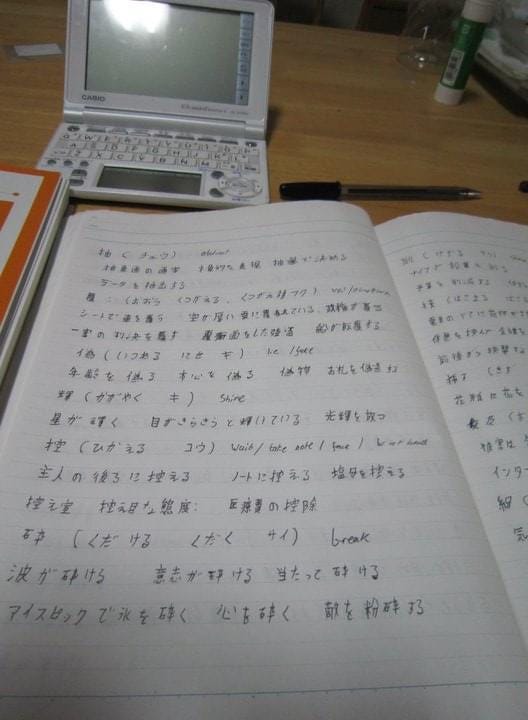

I then started copying all of my textbooks into notebooks, making sure I removed the English readings from the words and leaving only the hiragana and katakana. This was a very time consuming process and I was probably doing the stroke order of all the characters completely incorrectly, but I was learning a lot as I was doing this.

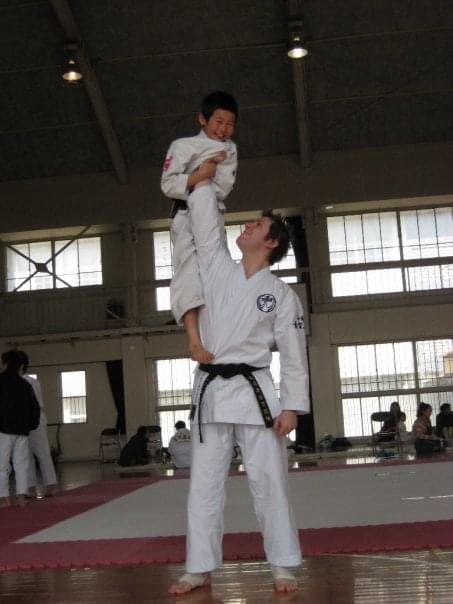

I was surrounded by Japanese people (some of whom were English teachers) so if I had questions, I could ask. I also started studying karate in a local dojō (the instructor spoke English but refused to do so unless I really needed help), so I could go out and practice what I learned with others in a practical setting that I enjoyed. In the evenings I’d often go out to a 立ち飲み屋 (tachinomiya : standing bar) near the train station with a dictionary an a notebook to try to communicate with the local salarymen as best as I could. (Although I don’t drink alcohol anymore, I did back then and it made communication smoother because I didn’t care if I made mistakes).

Underlying all of this, I used some software to do some drills (which I’ll go into a little further down). Using digital flash card programs are very useful for language learning and the one I use, I can’t recommend enough.

I started studying in August 2006 and after four years of grinding I passed the 日本語能力試験 (Nihongo Nōryoku Shiken: Japanese Language Proficiency Test (JLPT)), N2, which is the second highest level. (JLPT link here). I don’t have the highest level (N1) but that’s mainly because I went off to do other, more focused things that don’t help me pass the JLPT. (I went on to do a PhD in medicine at a Japanese university, which means I can explain a lot of things that will never show up on the JLPT, but I don’t have enough general knowledge about poetry/literature/history/economics etc., to pass N1 without dedicating a lot more time to studying something I’ll never need).

The reason why I said that it might be difficult to replicate what I did is that I was surrounded by the Japanese language and it was essential for me to learn. If you don’t have the resources or that necessity driving you, it might make it a bit more difficult to learn. However, I believe if you have interest, a good strategy, and good resources you can be successful.

4. Strategy and resources

There are some people out there that will claim you can learn Japanese without studying the writing system. Don’t listen to these people. I originally was planning to learn just how to speak but I gave up on that because I found that learning how to write made it easier.

You are going to need to get a textbook of some kind. The book Basic Japanese for Students: Hakase 1 (Amazon link here) is one that I recommend (because it’s one of the books I used). There are other book series you can try but this one was aimed at teaching people in Japan the basic mechanics of the language.

While you are using your textbook, I recommend dedicating some time to drill hiragana and katakana by writing it down over and over again until you remember it. One dedicated weekend with a block of paper, a pen, and a lot of coffee, and you will be able to more or less remember all of the hiragana (start with hiragana first). Another weekend and you’ll get katakana.

I know that studying like this is an absolute grind, but physically writing it out will help with retention. If you want to quickly drill by reading alone, you can use Kanjibox (link here) to answer quick fire questions on kana readings. I also used this for revision (not just for hiragana and katakana, but also for kanji). It wasn’t available on iOS back when I was learning but it’s advanced a lot now.

Exposure to the Japanese language language is important, but enjoying that exposure is also very important. I did a lot of brute force grinding to learn Japanese, but I also went out to practice martial arts, and communicate with people. I was also into Japanese horror movies and anime when I was in the UK, so watching these things also gave me additional (enjoyable) exposure to the language. If you only grind, you’ll get frustrated and may want to quit, so finding a way to enjoy your exposure to Japanese is a must.

Finally, I think it’s important to mention the Anki flash card program (link here). I have spent hundreds, perhaps even thousands of hours using Anki. With this program you are able to create and review flash cards to help you remember things more efficiently. You can use this for pretty much anything related to Japanese, including reading, grammar, kanji, vocabulary, listening (you can import sound files). I’ve also used Anki to pass other non-language related exams (I have a Project Management Professional (PMP) Certification, which I used Anki to study for). My recommendation with Anki is to use multiple decks, some related directly to the textbook you are studying, and others related to things you find out there in the world. That will allow you to focus on what you are studying (especially if you are aiming to get a qualification in Japanese).

5. Japanese qualifications

The JLPT is pretty much the gold standard for working in Japan. N5 is the easiest and N1 is the hardest. Setting yourself a goal to get these qualifications and working towards them can either be a good motivator or can suck the fun out of learning. The exams only happen twice a year and need to be done in person. It’s up to you whether you want to go for these or not, but I would say that unless you want to work in Japan and need it for your CV they aren’t necessary.

6. Final thoughts

Many people say that for English native speakers, it’s difficult for us to learn Japanese and languages like French and German are much easier. But for me, I can speak Japanese but can’t speak French or German, regardless of the public perception of the languages. This is mostly due to the fact that I’m interested in Japanese and applied myself to studying it.

The strategies and resources I listed in this article are what worked for me. Other people may have completely different approaches, and that’s fine. I’m not here to be a language teacher that is able to give everyone the best tips on how to learn. In my opinion, enjoying something in a language, and working hard to get better at that language is how you end up being able to be successful.

The whole ethos of my blog is 文武両道 (bunburyoudou : The path of the scholar and the warrior). I studied the Japanese language (the 文 (bun : literature) part), while studying martial arts (the 武 (bu : martial) part). Walking a both roads (両道 : ryoudou) at the same time helped me achieve success in both areas. Because I wouldn’t be able to study martial arts in Japan if I couldn’t communicate, and I wouldn’t be able to communicate if I didn’t have martial arts as the driving force to learn. It’s all a balance.

If you’ve read this far and have decided that you really want to take the plunge and start studying Japanese, I wish you the best of luck. My comment section is open if you have any questions.

Thank you very much for reading. If you enjoy my work please share it with someone you think would also enjoy it.

If you aren’t subscribed, please sign up to keep up to date.

If social media is more your thing I’m active on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

And if you are looking for ways you can support my work please check out the page below:

Osu!

Anthony

I am envious of your dedication and the opportunities you have had. Keep up the excellent work with these Substack pieces.

👍