Bunkai (分解) Obsession

You keep using that word, I do not think it means what you think it means.

“Bunkai” is a word I see a lot when interacting with (predominantly) English speaking martial artists. You might notice that I used the word “bunkai” in Roman characters rather than using my usual style of adding a Japanese word first. The reason why I’m doing that is because I have the impression that “bunkai” (when used by English speaking karate practitioners) means something along the lines of, “to break down, analyze, interpret, and apply sections of kata.” I think that is a pretty reasonable definition, but if you have a better idea please drop it in the comment section. There is a Wikipedia page about the term ‘bunkai’ (which can be found here), but please note that although the Japanese word 分解 (bunkai) is included, there is no Japanese language version of this page (click the languages tab to check). This is odd because you would think that if bunkai, “is a term used in Japanese martial arts,” then there would be a Japanese Wikipedia page for it.

It seems to me that ‘bunkai’ has pretty much become an English word with a meaning that is similar to (but not exactly the same) as the Japanese term. That’s mainly because the meaning of ‘bunkai’ in English seems to be a bit more complex than the Japanese term. In this article I’m going to look at the term ‘bunkai’ and give you my thoughts on this concept.

Some language breakdown of the term 分解 (and related terms)

The word 分 (bun) is a word with multiple uses in Japanese. It’s one of the first words you learn as a student of the Japanese language and it’s very versatile. I’m not going to quote all the meanings here (please check a dictionary like this one) but to look at it broadly it means ‘part.’ An interesting aspect of this kanji is that it looks like a sword (刀 (katana: sword)) cutting something into two parts (very simple). The second kanji is 解 (kai), which means to solve, to explain, to answer, to analyze. This kanji looks a lot more complicated than the first one (but is not actually that complex). It’s made up of 角 (kaku: angle), 刀 (already discussed) and 牛 (ushi: cow). Although 角 means ‘angle’ (amongst of other things) it should be noted that the image of it is supposed to be like a drawing table (where someone would measure angles). Next to the table you have a cow (牛) with a sword (刀) above it. (In the kanji 分 the sword has moved down and divided something into parts). That makes 解 an expression of putting a cow (牛) on top of a table used to analyze things (角) then cutting it apart with a sword (刀) to find something out (to solve/explain/answer/analyze something). Interestingly the word for dissection 解剖 (kaibou) uses the same kanji as the kai in bunkai but the second kanji means to divide (and contains the knife/sword radical).

It should be noted that in Japanese there are several words that mean ‘analysis,’ each with a slightly different nuance. I spent several years working in a lab and as a result I needed to use some of these terms quite often. We know 分解 is the word used for ‘analysis/disassembly’, but there are two other words that are used for analysis; 分析 (bunseki) and 解析 (kaiseki). The only new kanji introduced here is 析 (seki), which is a tree 木 (ki) with an axe radical 斤 (kin) next to it. 析 (seki) is another kanji that means analyze is more along the lines of cutting down a tree with an axe and counting the rings. Bunseki and kaiseki are terms that Japanese people may have trouble understanding the nuance of but basically, bunseki is 'to break something down (divide it into smaller elements) and clarify its nature, structure, etc,’ and kaiseki is ‘To unravel things in detail and study them systematically and theoretically.’ (Credit to this blog (Japanese only) for helping me sort these words out).

The reason why I bring up the other terms for analysis is to highlight the fact that in Japanese there are multiple words for analysis, each with a different nuance. The word 分解 (bunkai) means analysis/disassembly and I agree with that. I would say however that taking simply taking something apart is a much more simplistic analysis than what 分析 (bunseki) and 解析 (kaiseki) represent (since bunseki is often used for things like analytical chemistry and looks deeply into the nature and structure of what is being analyzed, and kaiseki is often used in data science or statistics to identify trends in data and make theorize what it means).

In interesting observation on Google

In the introduction paragraph I mentioned that bunkai is a term used most commonly (though potentially not exclusively) by non-Japanese karate practitioners. One interesting experiment you can do with this is to do a Google image search for the word ‘bunkai,’ and then do another Google image search for the term 分解. In my case, when I search for ‘bunkai’ I get a lot of images of people doing karate, and when I search ‘分解’ I get pictures of electronic devices being disassembled. I added a couple of screenshots here but please try this for yourself.

My experience with ‘bunkai’ in Japan

Please note that I included some anecdotes in this section. So take it for what it is. I’m sure there are some people out there with contrary anecdotes and trust me, I’m already bracing myself to hear about those. I’m sure there are instructors that use the word ‘bunkai’ all the time. But that has not been my experience and I am writing this article based on confirmable linguistics and reproducible observation, in addition to presenting my own anecdotes and opinions.

Back when I practiced Wadō Ryū I had the opportunity to train with 大塚 博紀 (Otsuka Hironori the second) several times. (Please note that I am referring to the son of the founder of Wadō Ryū, not the founder of Wadō Ryū). Otsuka Sensei would often give detailed explanations about applications of karate but I have never heard him describe anything as ‘bunkai.’ I asked him specifically about the word ‘bunkai’ in a seminar I was attending (I was the only foreigner there) and I got a bit of a rebuke from him which included the phrase, “Why do foreigners keep asking me about this?!”

The word that is generally used in this situation is 応用 (ōyō/ouyou: Application). (The sound characters used for this are ‘おうよう’ (o-u-yo-u) but I have also seen ‘oyo’ used when writing this in English). The word “oyo” is used on the bunkai Wikipedia page and is described as “extracted fighting techniques” according to this reference. This isn’t correct by the way, because 応用 is not fighting technique specific and is used to describe the application of any theoretical concept. I have heard the word ‘ōyō’ used in many different circumstances and across many different styles (not just karate but in non striking related styles), while training in Japan, but ‘bunkai’ isn’t really something I have come across to any great degree (beyond my experience of being rebuked by Otsuka Sensei).

I have a feeling that the term may have come from manuals where photographs of people doing karate were taken and the photograph was labeled as a “breakdown.” This is a reasonable use of the word 分解 because it is looking at a single snapshot dissected from the entirety of the kata. It makes a lot of sense when written down. This word may have been written as BUNKAI, when translated into English but it may also have been translated as, breakdown/figure.

Recently (and I mean within the past few years) the term ‘bunkai’ in relation to karate seems to be increasing little by little in Japan. It might be due to organizations like the World Karate Federation (WKF) popularizing it (note that the WKF headquarters is based in Spain). Personally, I don’t think ‘bunkai’ is the correct word for what they are doing because it is not a simple breakdown. What they are doing looks like an application demonstration of a kata rather than a simple breakdown. But this is something that people don’t seem to want to hear (especially if talking extensively about ‘bunkai’ is part of their brand or image).

Skilled physicians vs skilled anatomists. Application vs theory

I have a PhD in medicine, but I’m not a physician. My qualification is quite confusing to some people because if you are a doctor in the field of medicine it sounds like you are able to treat patients. My explanation of the difference has been that I’m ok at chopping things up but I wouldn’t be confident in putting them back together in working order again. Nor would I be qualified. I am simply a researcher that is able to analyze and dissect things and (if my experiments work well) maybe get some meaningful knowledge from my explorations.

Someone who is skilled at anatomy may be able to name every single structure of the human body but they might not be equipped to deal with how it works in a living patient. Physicians are skilled in ways that anatomists are not regardless of the skill of the anatomist. The other way round is also true. That’s not to say that there’s no utility in the study of anatomy, but I think people need to be real and draw clear lines about what is theory and what is practical application.

The dangers of going too deep into rabbit holes

Looking at kata, pulling out movements from them and practicing with a partner is a perfectly legitimate way to train. I am an Ashihara Karate practitioner and one thing I like about this (non-traditional) style is the fact that there are strong connections between the 基本 (kihon), 型 (kata), and 組手 (kumite). The basics (kihon) are the fundaments you work on as exercises, the Ashihara kata are drills for specific fighting techniques, and the kumite is the application of all the principles. Ashihara Karate does not use traditional kata but uses combination drills as kata specific for the style (which are very simple, effective, and need little interpretation).

There is definitely some utility in exploring the deeper meeting of traditional kata. You can certainly go down rabbit holes with some of these, but I would argue that there are dangers in going too deep into these, getting lost, and eventually getting consumed by something sinister that has crawled its way inside.

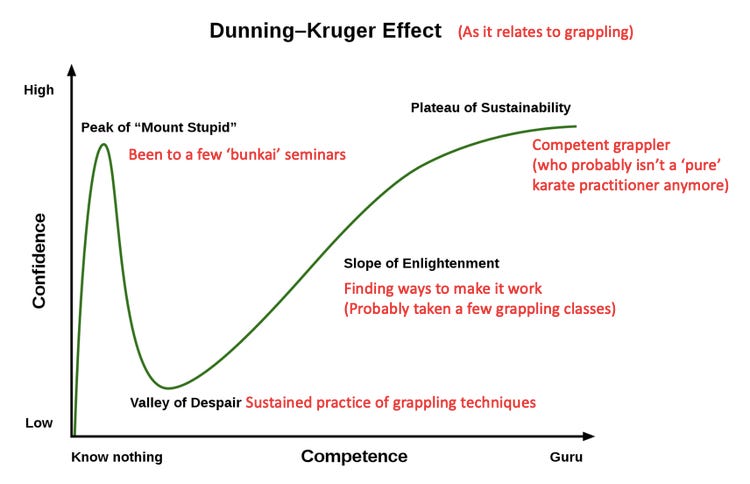

I’ve heard many times that there are ‘hidden grappling techniques’ in kata but they need to be analyzed and pulled out before they could be understood (bunkai’d out? Is that even used?). In my opinion, attending an occasional seminar on kata bunkai is not going to make you an expert in grappling. It could be a good introduction but diligent practice is required. If you want to be able to grapple you need to incorporate that as a fundamental part of your training. If not, it just seems like something additional to add to a striking art that may give you false confidence in your ability to grapple (see the Dunning–Kruger Effect). It’s better to know you can’t grapple and to stay away from grappling than it is to think you can grapple and end up getting wrecked by someone with actual ability. In fact, if you want to learn how to grapple it is better to go join a class that teaches grappling as a fundamental part of the system. You don’t need to quit karate to do that. We are living in a world now where it is possible to access multiple styles, so why not give it a go? You might think after getting thrown around a bit that maybe grappling isn’t for you and that you’ll stick to striking, but that in itself is a very important lesson. (And that is of course, completely fine. I used to have spiky hair but I’ve had chunks of hair accidentally ripped out while wrestling. So I prefer my hair to be very short these days).

Another thing that I would caution people is the concept of reverse engineering. Some people may not even realize they are doing this. I once saw what I would describe as a nauseating video which took clips of people in active martial arts matches (UFC, Pride etc) and then played clips of someone doing a kata to show that all of the punches, kicks, throws, grapples etc., were ‘IN THE KATA.’ There is an implication that karate is a perfect, complete style and if you just practice kata properly you’ll be able to just do everything. I’m not a subscriber to this mode of thinking. I’ve also seen people that have learned other techniques outside of karate and know them to a complement level who then try to demonstrate that the technique they learned elsewhere is in fact, “in a kata.” I’m not quite sure what they are trying to demonstrate here but to me it’s just a demonstration of how abysmally kata transfer techniques across to their practitioners. If I can learn a choke pretty quickly by going to a grappling class, why on earth would I care that a kata contains that choke if you look at it from the right angle?

Clarification

Let me just clarify the positions that I’ve laid out in this article, because I want people to be arguing with my actual position rather than a straw man version of it.

I absolutely do think there is utility in diligently practicing kata applications to the point that techniques go from a theoretical principle to a technique you can naturally apply.

What I don’t agree with is the dogma associated with the practice of ‘bunkai.’ I do not believe that karate is a perfect and flawless system with every possible fighting situation there is distilled into a few movement routines. If something is so complicated that it needs a lifetime of study to be able to understand it properly, it is not a useful way to deliver a message. If you look at people in the UFC dynamically punching, kicking, and grappling each other and think, “That’s just like a move I saw in naihanchi,” I think you may be deluding yourself.

Of course there is some utility in becoming essentially an expert in the anatomy of kata. But when I come across phrases like, “This is the bunkai of heian shodan,” or, “This is my bunkai of saifa,” I think there is a very specific thing that is going on here. When I hear ‘bunkai’ described like that it comes across as a training style that might as well have it’s own trademark at this point (Bunkai™?…You heard it here first. If you see that on a T-shirt being sold on any online stores by any of the Bunkai™ personalities out there they probably stole the idea from me).

I’d actually much prefer it ‘bunkai’ was referring to a specific snapshot of a kata and ‘ōyō’ was the application of technique.

I believe many practitioners do use this nomenclature, but others don’t seem to want to use these terms because they have dedicated too much of their career to calling everything related to the breakdown and application of kata, BUNKAI.

Take home messages

I would encourage people to keep practicing karate in whatever way they see fit. However, I would also ask people to make sure they are not missing the forest for the trees (or at least the specific tree with 分解 carved into the bark). There are certainly some interesting rabbit holes to explore, but those rabbit holes can also turn into pitfalls with hiding sinister things waiting to consume you. And although there are some very skilled karate anatomists out there that are able to dissect karate in very interesting ways, remember that dissecting something that has been laid out on the table is very different to learning from a living, breathing organism. Theory is great but it requires skill and dedication to make true 応用 (ōyō: Application) a reality.

Thank you very much for reading. If you enjoy my work please share it with someone you think would also enjoy it.

If you aren’t subscribed, please sign up to keep up to date.

If social media is more your thing I’m active on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

And if you are feeling generous but don’t want to commit to a monthly subscription, you can send a small donation to my Buy me a coffee page below.

Osu!

Im reliably informed that Sensei Frank Brennans fave kata is Heian Nidan. So what do i do when trying to learn a new kara, Jitte for example, if i dont try to understand what it is Im doing? What is that?

Enjoyed reading your article, especially the kanji explanations. Two things come to mind: First that your essay in its entirety is classic karate analytical process and thinking. Second, that at this point in my journey, I view bunkai as essentially a Rorschach inkblot test with multiple, likely infinite, interpretations and perspectives. You can take sequences as such. You can scramble them. And you can cut, copy-and-paste strings and techniques across then kata menu. Further, don't forget that all of them can be inverted (left to right). For me, that's the beauty of the whole thing which keeps us engaged.